Introduced during a period of record high energy prices, the UK Government's energy support schemes came to an end on 31 March this year. Evaluating emergency measures such as these purely on their value for money is difficult, as the policy was intended to serve multiple purposes.

At the time of introduction, the fundamental affordability of energy was in question. High energy prices were one of the catalysts for rising interest rates, heralding an economy-wide cost of living crisis. The government aimed to calm markets and provide a measure of manageability for household and business budgets. From the perspective of the householder, with that in mind we must ask ourselves, did the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) and Energy Bill Discount Scheme (EBDS) (successor to the Energy Bill Relief Scheme) deliver what they needed to? In this piece, we will assess the schemes’ effectiveness by looking at subsequent market trends, contextualising the cost relative to government spend, and considering what happens next.

EPG and EBDS versus Market Peak Prices

The EPG and EBDS were introduced to provide substantial relief to consumers during a period of soaring energy prices. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, and subsequent disruptions to energy supplies as countries sought to divest from Russian fossil fuels, resulted in significant increases to electricity and gas wholesale prices.

The decision by the government to launch what was an unprecedented, post-privatisation intervention in the energy market was largely led by pressures on domestic energy bills, and occurred against a backdrop of a succession of supplier failures and lingering questions about the relevance of the Default Tariff Cap. However, as with the Default Tariff Cap, the EPG was not an absolute upper limit on bills for domestic customers, but rather a ceiling on the unit rates for gas and electricity that was revised quarterly – essentially a cap on the cap. A different approach was applied for prepayment customers, but the intention was the same, namely to limit the impacts of the energy crisis on bills.

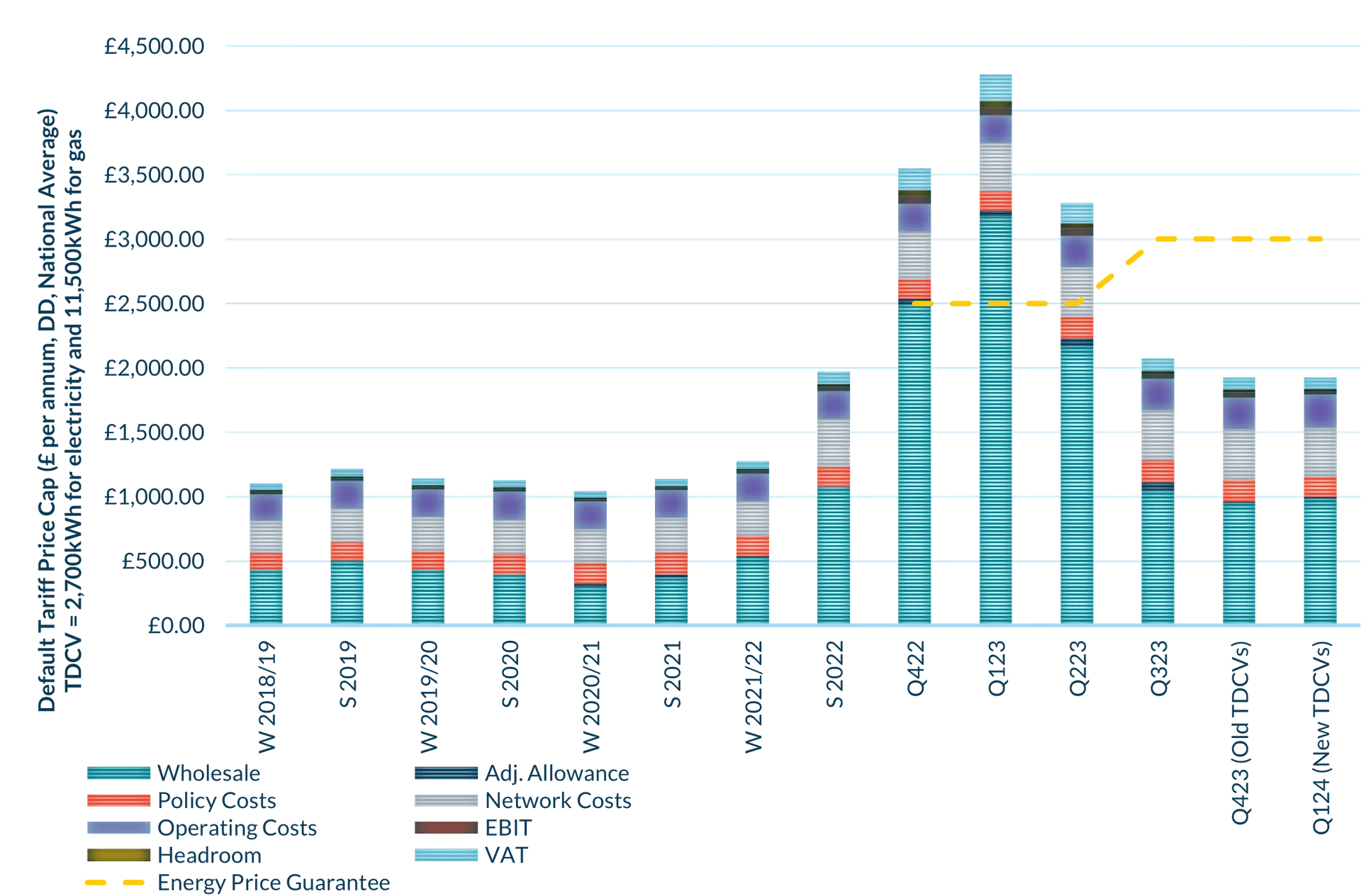

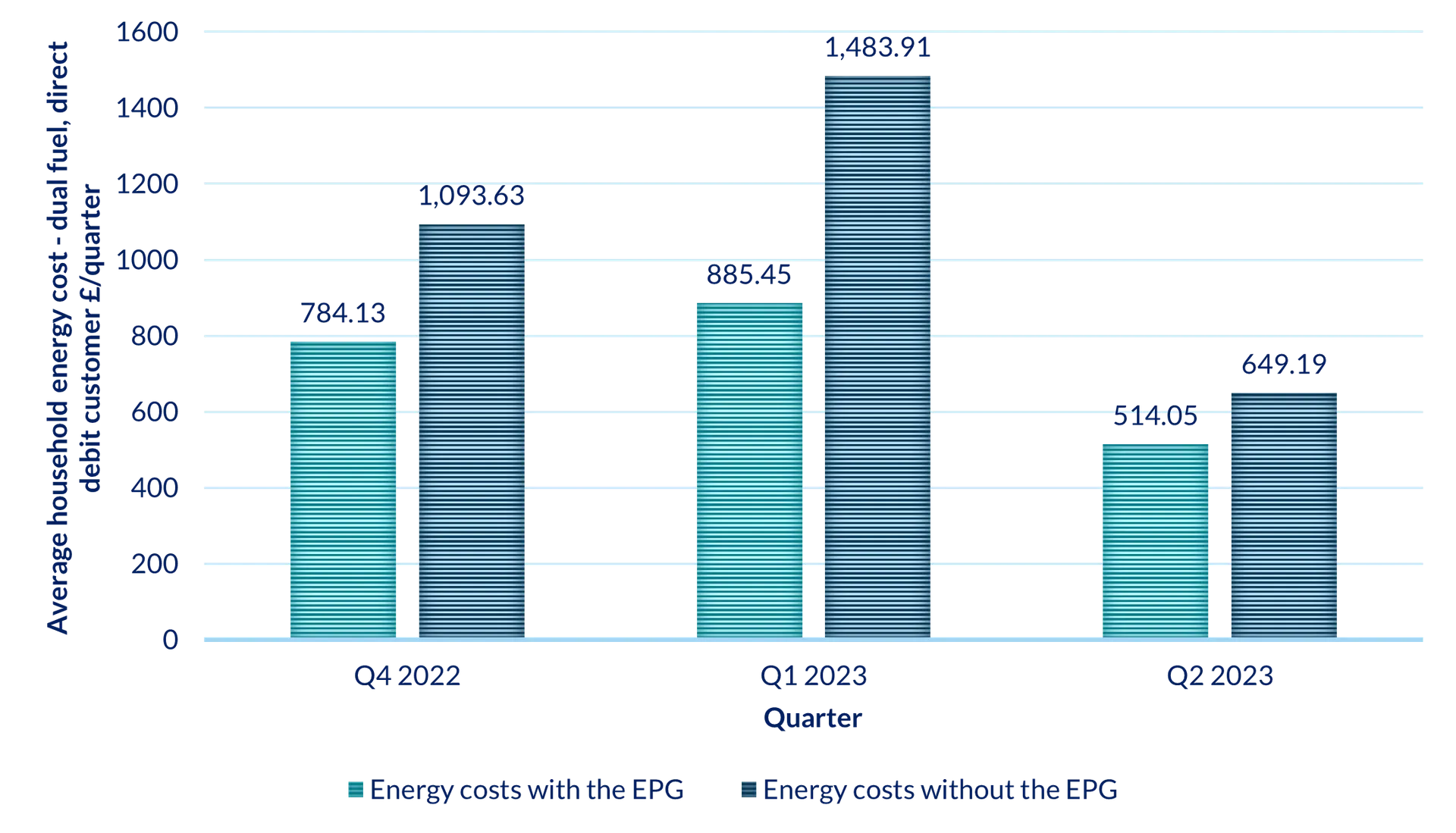

In absolute terms, the EPG was set at £2,500 per annum for a typical household – initially for the six month period commencing October 2022, with a scheduled increase to £3,000 from April 2023 that was subsequently delayed until July 2023. Given the elevated levels of billpayers supplied via the Default Tariff Cap, the EPG became the de facto tariff cap for the nine month period from October 2022 to June 2023 inclusive, at which point the Default Tariff Cap took effect once again (Figure 1). Our analysis shows the introduction of the EPG saved a typical household just over £1,000 (Figure 2), this figure being based upon profiled gas and electricity consumption over the period and the difference between the Default Tariff Cap unit rates and those for the EPG.

Figure 1: Default tariff cap vs. EPG support (dual fuel, direct debit customer, national average)

Source: Cornwall Insight analysis, Ofgem

Figure 2: Default tariff cap vs. EPG support by quarter (dual fuel, direct debit customer, national average)

Source: Cornwall Insight analysis, Ofgem

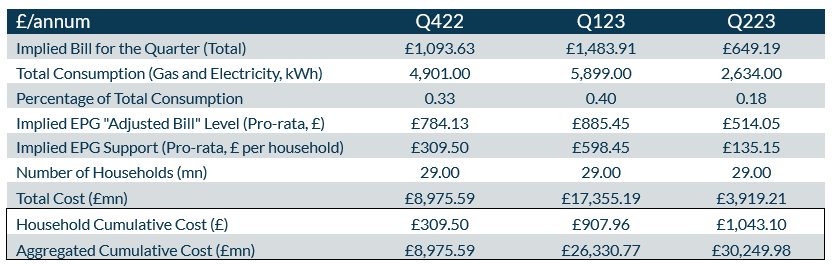

Cost of the EPG

In terms of the cost of the EPG, we can assess this by examining the implied consumption over the nine month support period and what a typical household would have paid under the cap compared to the EPG. We have examined this on a quarter-by-quarter basis (mirroring the cap and EPG approach) and examined the implied cost for an assumed 29mn dual fuel households. Our analysis indicates that the cumulative cost of the EPG was just over £30bn, with the benefit to a typical household being just over £1,000 (Figure 3).

However, this excludes the cost of the Energy Bill Support Scheme (EBSS), which represented £400 of additional support for households, with specific eligible households receiving even more support. Applying the EBSS across the assumed 29mn households implies an additional cost of £11.6bn, making the total cost of supporting household bills reach approximately £42bn.

Figure 3: Energy Price Guarantee (dual fuel, direct debit customer, national average)

Source: Cornwall Insight analysis, Ofgem, DESNZ

Overall, the EPG and EBSS met their objective of reducing the exposure of households to the effects of the surge in wholesale prices. This was done in a relatively light-touch manner as far as most households were concerned, with this process being managed through energy suppliers. That is not to say the scheme came without its challenges, with a more nuanced approach needing to be applied to certain customers and those that required access to Alternative Funding (AF).

Support for businesses came through the Energy Bill Relief Scheme (EBRS), which ended in March 2023, and was then replaced by the EBDS. Unlike domestic support, eligible businesses under the EBDS only received a discount on their electricity and/or gas bills if their contracted wholesale price exceeded a given threshold. In addition, there was an upper bound on the level of bill support, with any wholesale price above this threshold remaining the liability of the business.

As such, the EBDS was not as generous as its predecessor or the support for households, although there was additional support for Energy and Trade Intensive Industries (ETIIs). In establishing the EBDS, the government assigned a total spend limit of £5.5bn, of which it anticipated 60% would be spent on ETIIs. In total, the cost of the entire package of energy bill support was estimated at £69bn by the National Audit Office (NAO).

Did the support schemes cost a lot?

To put the measures into context, the 2024 Spring Budget sets out department budgets for 2023-24: the day to day running costs for NHS England are £163 bn, the Home Office £19 bn, Defence £35 bn. The scale of expenditure is substantial, although it should be noted the speed with which the measures were introduced. The policy measures were inherently defensive, driven by a desire to protect consumers from the energy price crisis.

Long term government plans intend to deliver energy security, insulating homes and businesses from high and volatile international energy prices. A more enduring question is the extent to which such large-scale support is feasible while also investing in new infrastructure and a decarbonised energy system.

The status quo is unsustainable

The energy market remains volatile, with global factors continuing to contribute to long-term uncertainty. With the EPG and EBDS concluding, there is a noticeable absence of a direct replacement policy, like a social tariff or equivalent for more vulnerable customers.

While Ofgem and DESNZ have sought views on the future of the Default Tariff Cap, the lack of extra post-crisis support for vulnerable customers remains evident. With a General Election on the horizon energy affordability may be an issue that political parties look to pursue. At the same time, the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) programme (and any future reforms to the cap resulting from Ofgem’s aforementioned workstream) has the potential to both bring benefits to consumers and to mitigate – or indeed avoid – the effects of future energy price spikes in the future. As such, the need for future interventions on the size and scale of the EPG and EBDS may be reduced as a result of REMA, at least its proponents might argue.

It is difficult to determine if the EPG and other support schemes ultimately represented value for money. The impacts on reducing consumer energy bills has been cited by the government as providing a key contribution to affordability during the cost of living crisis. Citizens Advice’s figures indicates that 5.3mn people were in debt to their energy supplier in January 2024, and 800,000 people went more than 24 hours without gas or electricity because they couldn’t top up their meter. Significant criticisms have come from businesses, with it being argued that the EBDS did not provide the same depth of support as its predecessor, and that the definition of ETIIs left some stretched businesses without sufficient support.

It should be noted that the schemes were deployed both swiftly and on a large scale in response to events that represented a once-in-a-generation challenge to the energy market.

However, the speed with which the schemes were introduced meant that they were inherently reactive, and therefore represented somewhat of a blunt instrument. Indeed, at the time the government highlighted that there was a risk that the schemes could provide support to those that did not necessarily need it. A more proactive approach to potential intervention by government would allow for a more targeted approach – thereby benefitting those customers in the greatest need and aiding long-run value for money.